At the beginning of David Foster Wallace’s famed commencement speech at Kenyon College in 2005, two young fish encounter an older fish as they are swimming along, and the older fish says to them in passing, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” As they swim on, one of the young fish eventually looks at the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”

The profundity of Wallace’s illustration has many applications, but I’m thinking today of how we swim in a culture of violence.

At almost the exact same time on Wednesday and hundreds of miles apart, two acts of violence occurred in school settings: a 16-year-old with reportedly anti-Semitic and white supremacist views murdered two high school students before taking his own life, and a 22-year-old with reportedly anti-fascist views murdered an enormously popular politically-conservative speaker on a college campus. And both happened on the day before the anniversary of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. The confluence of these terrible tragedies produced a flood of emotion, naturally, and many in their grief offered expressions like “this is not who we are” and “how did we get here” and “who have we become.” Sadly, my thoughts turned to Wallace’s little parable.

I am (always saddened but) no longer surprised by acts of violence, although I am often surprised when others are surprised by acts of violence. We live in a culture of violence, and I’m not talking about the United States of America (only), and I’m not talking about something that has occurred in the past few years, or even in our lifetimes. I believe that humanity itself, at least human civilization as we understand it, has historically and continually believed at its core that violence can make things better, that violence solves problems, that violence produces justice. We condemn certain acts of violence and condone (sometimes celebrate) others as good, and as a result, violence is as ubiquitous to our lives as water is to a fish.

Governments seek the death penalty under the banner of justice. Nations go to war under the banner of justice. Cartoons and movies and television series create heroes who beat the hell out of villains and in so doing make the world a better place. Logically, while we (can and should and do) condemn the actions of abusers and assassins and terrorists, it should not surprise us when others perform terrible, violent acts that they believe will somehow make something better, too. This is water, as Wallace might say.

Theologian Walter Wink called this “the myth of redemptive violence” and claims that this really is who we are, at least in the sense that this concept is the water in which we swim unaware.

I was a pastor in my early thirties when the 9/11 attacks shocked our nation. At the time, my job was to think deeply about Christianity and translate that into the life of a church. I recall that I quickly became troubled by the natural (and national) response to the tragedy. To be specific, I had understood that my faith tradition looked at war as a terrible event, although for many the just war theory stood as a reluctant option that was developed in an attempt to wrestle with the moral challenges with classic pacifism. All that went out the window quickly when our nation was attacked, and shortly, even preemptive attacks on nations unaffiliated with the attacks seemed justified by large swaths of Christians regardless of the wisdom of centuries of church teachings.

Wink clarified for me at the time that a belief that “violence is both necessary and effective for resolving conflict and achieving justice” may be a far deeper value for many who claim Christianity than Jesus’s call to “love your enemies.” Wink went so far as to claim that “[i]t, and not Judaism or Christianity or Islam, is the dominant religion in our society today.” I recommend his book “The Powers That Be” if you truly want to wrestle with his thoughts and address the “what-ifs” that probably come to mind first (i.e., What if someone breaks into your house to threaten your family? What if nobody stands up to Hitler?). Those are valid questions, and Wink takes them on, but that is not my point today. Instead, I simply point toward the ocean that we swim in together. Violence is an ugly word that we condemn in times of tragedy, yet violence undergirds and defines our culture, and we should at least be aware.

The diagnosis runs deep, and the prognosis is not encouraging, but after decades of wrestling I have adopted an approach to life that does not include despair. While I personally support pathways leading to fewer dangerous weapons instead of more, and while I long for vast improvements in mental health care, neither strike at the root of the redemptive violence mindset. So, what to do?

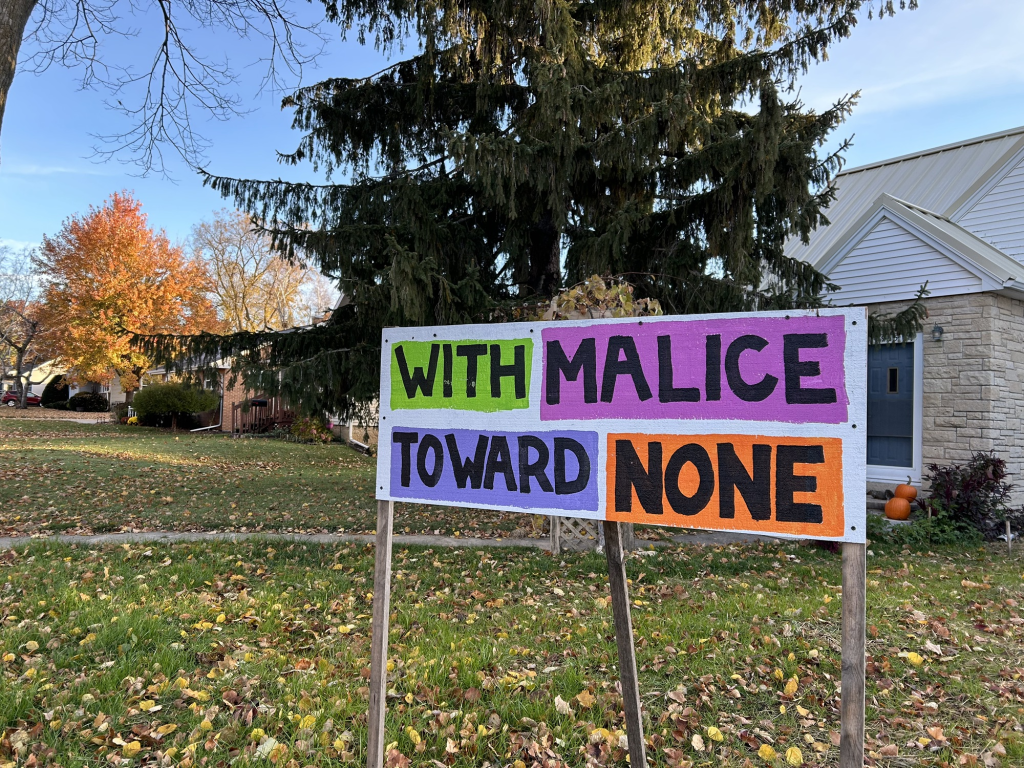

My choice is simply to reject violence in all its forms, including those popularly conceived of as redemptive. I choose, if you will pardon the metaphor, to attempt to live as a fish out of water.

How to do that is ridiculously complicated, but at least the why is not. Why I choose to pursue a path that rejects all forms of violence is because the ocean I would like to swim in is one where every human being is imbued with dignity and respect and worthy of love. With that perspective, violence is no longer an option because violence is inconceivable toward someone that you truly love.

I know. When someone told me I live in fantasy land, I nearly fell off my unicorn. But I’m not talking love in the silly sentimental sense. I’m talking love in all its messiness. The sort of love that will do the hard work of creative resistance, but never attack or demean or destroy. How can you attack someone you love?

This is how I still claim to be a Christian, despite myriad reasons to disassociate based on popular conceptions of what that means. I believe that indiscriminate love, which includes your worst enemies, is the heart of Jesus’s message, and I am bought in. I cannot imagine that such a radical thought would ever be popular, but I can imagine what it would be like if it were, and that is enough for me.

As nostalgia sets in at the prospect of leaving the law school, the privileges I enjoy become more pronounced. One of my favorites has been hosting the Interfaith Student Council.

As nostalgia sets in at the prospect of leaving the law school, the privileges I enjoy become more pronounced. One of my favorites has been hosting the Interfaith Student Council.