Confession: I struggle to keep up.

The well-orchestrated and rapid-fire actions of the second Trump administration are dizzying, and while I have many opinions on many issues, I just can’t seem to keep up. I have a job (that I love) that consumes a significant amount of time, and by the time I attempt to be informed enough to formulate thoughts potentially worth sharing, those issues are old news.

And to be honest, part of me wants to remain silent, partly from the dizziness of it all, but also because I recognize that President Trump and his party won the election and have a relatively short amount of time to make their case for remaining in power before the American people render a verdict at the midterm elections. But another part of me wants to speak out constantly, not only because I care about so many of the issues, but also because I recognize that silence contributes to a gaslighting effect for those that suffer from certain words or actions, including many friends from historically-marginalized groups that wonder if anyone sees their pain.

Despite the tennis match going on in my mind, I have something to say today that I hope will be heard.

I’ll probably lose some of you at the start when I reference Erwin Chemerinsky. Erwin Chemerinsky is dean of the law school at UC-Berkeley, and just the mention of Berkeley will lead some to tune out, but I beg you to stay with me anyway. Chemerinsky is a constitutional law scholar, on the liberal side as you might suspect, but if one can recall such a time, he was also a good friend of the late Ken Starr, a constitutional law scholar on the conservative side who was dean at the law school I chose to attend in 2008. Chemerinsky and Starr rarely arrived at the same interpretive conclusions, but they shared a love and respect both for each other and the United States Constitution.

The New York Times published a guest essay from Chemerinsky two days ago titled, “The One Question That Really Matters: If Trump Defies the Courts, Then What?” Please recognize this title question is neither liberal nor conservative but a question of constitutional structure that is simultaneously an existential question for the American form of government.

It is a short essay that I suggest you read, but I will share the highlights. Chemerinsky writes:

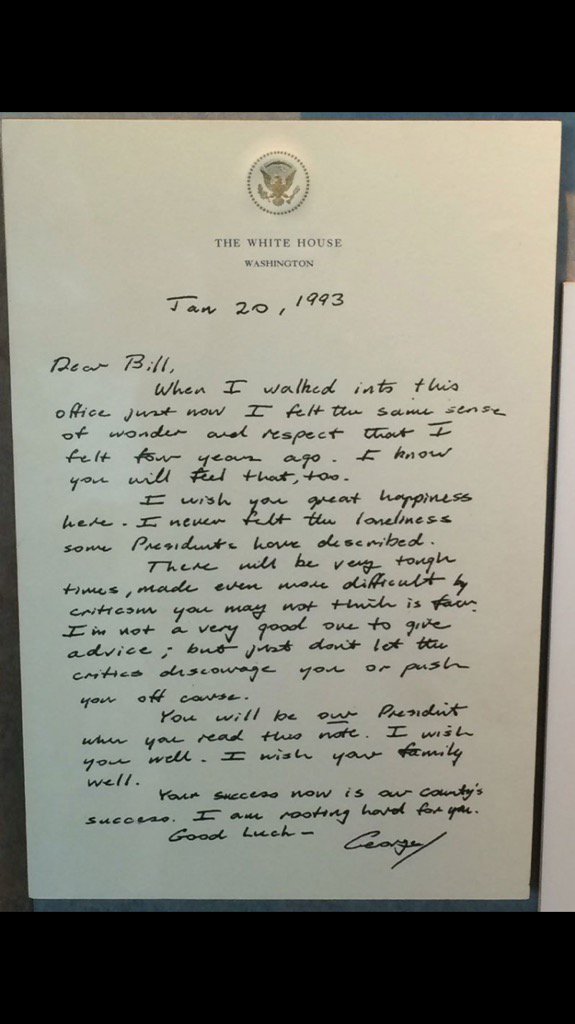

“It is not hyperbole to say that the future of American constitutional democracy now rests on a single question: Will President Trump and his administration defy court orders? . . . [T]he Constitution gives judges no power to compel compliance with their rulings — it is the executive branch that ultimately enforces judicial orders. If a president decides to ignore a judicial ruling, the courts are likely rendered impotent . . .. It is unsettling even to be asking whether the president would defy a court order. Throughout American history, presidents have complied with mandates from the courts, even when they disagree . . .. [T]here are no definitive instances of presidents disobeying court orders. The line attributed to Andrew Jackson about the chief justice, that “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it,” is likely apocryphal . . .. In addition, modern scholarship has undermined the story that Abraham Lincoln defied an order from the chief justice invalidating a suspension of habeas corpus during the early days of the Civil War . . .. Thus far, the Trump administration has given conflicting signals as to whether it will defy court orders. On Feb. 11, Mr. Trump said, “I always abide by the courts, and then I’ll have to appeal it.” . . .But just one day prior, Mr. Trump posted on social media, “He who saves his Country does not violate any Law.” . . . The reality — and Mr. Trump and those around him know it — is that he could get away with defying court orders should he, ultimately, choose to do so. Because of Supreme Court decisions, Mr. Trump cannot be held civilly or criminally liable for any official acts he takes to carry out his constitutional powers. Those in the Trump administration who carry out his policies and violate court orders could be held in contempt. But if it is criminal contempt, Mr. Trump can issue them pardons . . .. Defiance of court orders could be the basis for impeachment and removal. But with his party in control of Congress, Mr. Trump knows that is highly unlikely to happen. If the Trump administration chooses to defy court orders, we will have a constitutional crisis not seen before. Perhaps public opinion will turn against the president and he will back down and comply. Or perhaps, after 238 years, we will see the end of government under the rule of law.”

I have repeatedly emphasized Chemerinsky’s question in private conversations for weeks now, and I wish I could elevate it above all the noise. It is an existential question for American democracy, and I want to have done my part at least to try to place it in the spotlight it deserves.

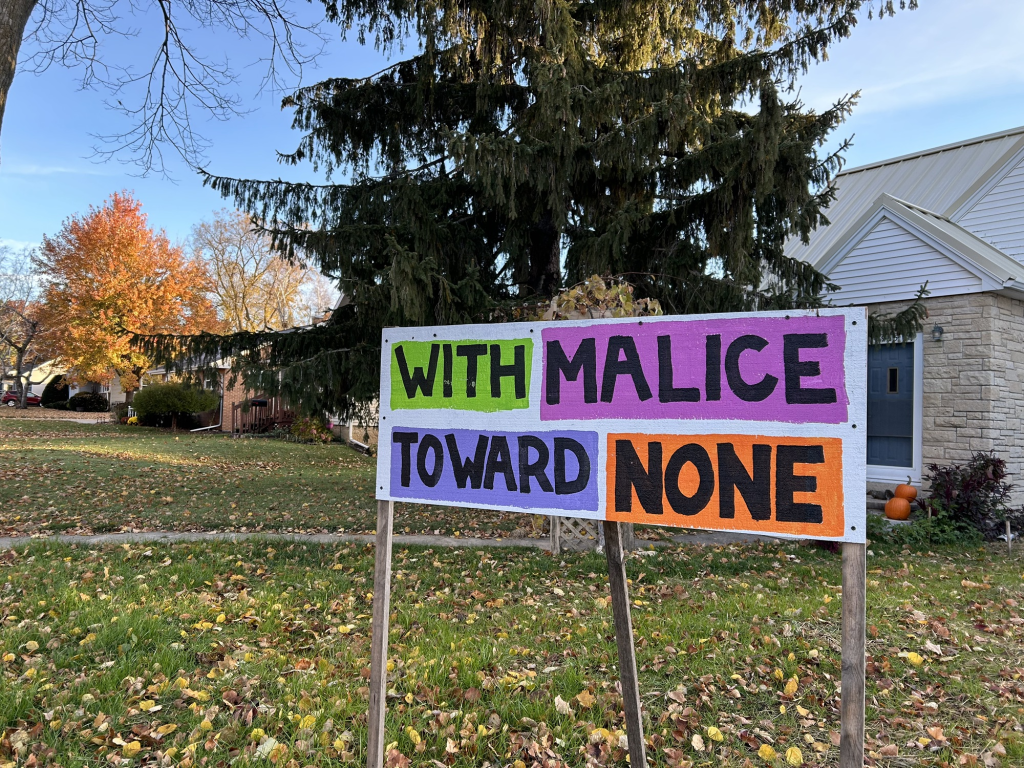

Let me be blunt: Presidents and parties come and go, but if any American president, ever, adopts an approach that defies the decisions of the courts, then we no longer have “the rule of law,” which has been the central feature of the United States government since the Constitution was adopted in 1787.

President Trump has famously said many things, including:

- “I can find a cure to the most devastating disease . . . or announce the answers to the greatest economy in history or the stoppage of crime to the lowest levels ever recorded and these people sitting right here [Democrats in Congress] will not clap, will not stand, and certainly will not cheer for these astronomical achievements.”

- “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose [MAGA] voters.”

Unfortunately, I think that for many he is correct on both counts. But I hope not for everyone.

I know full well that for many the support of a political party or a specific political leader is unwavering. But I hope that is not true for all. I hope that for many there are certain lines that cannot be crossed. And for anyone that values democracy as a form of government, this question regarding a respect for the “rule of law” has to be at the top of the list.

As nostalgia sets in at the prospect of leaving the law school, the privileges I enjoy become more pronounced. One of my favorites has been hosting the Interfaith Student Council.

As nostalgia sets in at the prospect of leaving the law school, the privileges I enjoy become more pronounced. One of my favorites has been hosting the Interfaith Student Council.