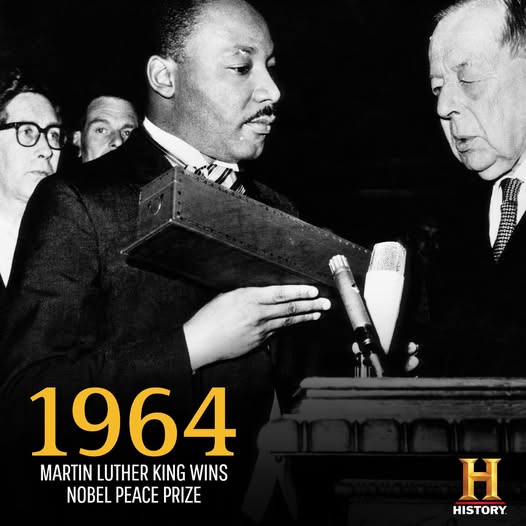

“Sooner or later all the people of the world will have to discover a way to live together in peace . . . If this is to be achieved, [humanity] must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love.” – Martin Luther King (Acceptance Speech, on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, December 10, 1964)

On the eve of the 2024 presidential election, I referred to a comment stating that the outcome of the election would say more about the American people than the campaigns themselves, and I believe that turned out to be accurate. The year since the subsequent inauguration has exposed disturbing collective values. I do not in any way believe that this administration invented revenge, aggression, and retaliation, but it has unapologetically modeled those human inclinations (e.g., Comey; Greenland; flipping off an autoworker; respectively).

The strange recent peace prize headlines serve as a poignant case study on this eve of the holiday that honors Dr. King.

In late 1964, King traveled to Norway to accept the Nobel Peace Prize. He opened his speech by making it clear that he accepted the award on behalf of the Civil Rights Movement, not himself, and then wondered why the award was given “to a movement which is beleaguered and committed to unrelenting struggle; to a movement which has not won the very peace and brotherhood which is the essence of the Nobel Prize.”1 His conclusion was that the award was, in fact, “a profound recognition that nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral question of our time – the need for man to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to violence and oppression.”

Later in King’s acceptance speech, in a passage that I feature at the beginning of this essay, he predicts that the world will eventually be forced to discover a way to live in peace, and that this elusive state will require a method of conflict resolution that “rejects revenge, aggression, and retaliation” — three popular methods that you spot easily simply by watching the daily news. Creative nonviolence is King’s answer, of course, and if you find that intriguing, don’t miss his next line: “The foundation of such a method is love.”

I know that peace and love is a tie-dyed t-shirt, but here is what I also know: Revenge has not proven to be a reliable pathway to true peace. Neither has aggression. Nor has retaliation. And I know it is a Beatles song, but I truly believe that not only is love our deepest need, but it is also the foundation for any desire we have for a world where peace and justice exist.

I always try and regularly fail to look at politics objectively. I began my professional life over thirty years ago teaching courses like history and civics, which then morphed into full-time ministry where I wrestled with theological approaches to complicated issues. My meandering life later wandered through law school, which added new layers to my way of thinking. Eventually I assembled my own framework for interpreting the world, and although that framework remains malleable, once assembled it has more or less hovered in the same general neighborhood.

All that to say, the annual Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday means more to me than a day off work (for some!) and a day to trot out one of his famous quotes. Instead, I identify with his fateful decision to adopt and promote creative nonviolence as the path to justice, and I arrived there through my admiration of Jesus, too.

It is incredibly difficult to love enemies. It is an outright radical concept, and it is practically impossible even to catch a glimpse of it on the national stage right now. And it does not surprise me that most find the concept ridiculous, if not repulsive. I just happen to believe, like Reverend King, that it is the secret sauce. More than a tie-dyed t-shirt, it is messy, painful, and can get a person killed. But, I believe, the secret sauce nonetheless.

So beyond the bizarre peace prize stories in recent headlines, for tomorrow’s holiday I look back to 1964 and say establish your own deeply-held interpretive framework for navigating this old world, but here’s a word for the framework espoused in Oslo by Reverend King that believes in the foundation of love for all people, even enemies. I have discovered that any love-inspired action that I achieve feels like a step in the right direction, and noticing even hints of that in our nation’s political discourse right now is a long shot.

- This posture, of course, is antithetical to an American president that said earlier this month, “I can’t think of anybody in history that should get the Nobel Prize more than me.” ↩︎

“I had my first racial insult hurled at me as a child. I struck out at that child and fought the child physically. Mom was in the kitchen working. In telling her the story she, without turning to me, said, ‘Jimmy, what good did that do?’ And she did a long soliloquy then about our lives and who we were and the love of God and the love of Jesus in our home, in our congregation. And her last sentence was, ‘Jimmy, there must be a better way.’ In many ways that’s the pivotal event of my life.” – Reverend James M. Lawson

“I had my first racial insult hurled at me as a child. I struck out at that child and fought the child physically. Mom was in the kitchen working. In telling her the story she, without turning to me, said, ‘Jimmy, what good did that do?’ And she did a long soliloquy then about our lives and who we were and the love of God and the love of Jesus in our home, in our congregation. And her last sentence was, ‘Jimmy, there must be a better way.’ In many ways that’s the pivotal event of my life.” – Reverend James M. Lawson