I confess a deep sadness following last week’s presidential election. It is a personal sadness, sure, but it is far more on behalf of those from historically-marginalized groups that feel especially vulnerable and afraid due to a resounding national stamp of approval for a candidate famous for hateful rhetoric offered in their specific direction. E.g., Stand back and stand by. Black jobs. Grab them by the ____. Too many direct quotes about specific women’s bodies to list. Mocking a reporter with arthrogryposis. Muslim bans. Shithole countries.

I felt especially sad for my two amazing daughters. Their professional lives and personal hearts are dedicated to teaching children who live in poverty in the urban core and who are now facing a promise of mass deportation that will rip immigrant families apart. It is hard to imagine a fear more fundamental than a powerful government separating you from your family. It was hard enough for me to communicate with my heartbroken daughters as they went to work the morning after the election and know that they love children by name who are facing those fundamental fears.

My sadness expands recognizing that my personal religion, Christianity, generally speaking, is openly and willingly associated with the national stamp of approval for the hateful rhetoric. Although I disagree with their conclusion, I can understand the thought processes of those who saw the election as a “lesser of two evils” vote, but there is never cause for celebration following a lesser-of-two-evils vote. And yet lots of Christians celebrated this one with euphoric joy; saw it as an answered prayer; used words like anointed. I unfortunately opened Facebook the day after the election.

I have been on a thirty-year journey with faith and politics, a journey that began in the early 1990s with me a young, questioning adult and the simultaneous rise of the Religious Right as a political movement. As Evangelical (for lack of a better term) churches gravitated toward the proselytization of a political strategy, I was saved from dismissing Christianity and moving on entirely, in part, by stumbling upon the writings of Will D. Campbell who demonstrated for me that there was a different way to be Christian, and I concluded that for me following Jesus meant that I must love everyone, regardless. Both sides. All humans. Even enemies. Learning to “live reconciled” became an important phrase to me, as did “indiscriminate love.”

But that really messed me up. Loving everyone is a recipe for loneliness in a culture insistent on choosing sides, winners and losers, us and them. On one hand, I could see the pain felt by those that experienced decades of cultural condescension and blindness to class inequality from the Political (and Religious) Left while on the other hand growing increasingly cognizant of the centuries of pain felt by those that experienced the terrible injustice and marginalization perpetuated by the Political (and Religious) Right. So, I eventually learned to bite my tongue a lot, choosing instead to plant seeds, attempting not to alienate either side in an attempt to love and maintain relationships with everyone. I chose to work within a lot, behind the scenes a lot. And I felt guilty a lot for not doing and/or saying more.

My interpretation of Christianity remains, but in time I sought a quiet freedom from a life where I am not allowed to be fully authentic, and I am grateful for the wonderful feeling of liberation that I now experience. But given my own emotional reaction this week, and given numerous private texts and conversations with friends from all over the country that we made on our long journey toward personal liberation, my personal freedom seems self-serving and wholly insufficient.

But what to do?

That question has dominated my thinking, and I am grateful for anything I have heard and read from Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom in the aftermath of the election (like the full Daily Show interview). Dr. Tressie has helped me tremendously (and I thank my friend, Chalak, for telling me about her in the first place). And I have also benefitted from articles written by both David Brooks and David French after the election, white men from conservative backgrounds who through their columns have assured me that my visceral reactions to the election aren’t simply because I drank Kool-Aid at the Liberal Vacation Bible School.

Collectively, they pulled no punches in saying that chaos is coming but emphasized that despair cannot be allowed to be the mood for long. Dr. Tressie advised, “Don’t cry too long over a sinking ship,” and the subject of David French’s email read, “We don’t have time to waste time in despair.”

French wrote, “There’s a temptation to retreat. If you have a stable job, a good family and good friends, you can check out of politics. After all, politics can be painful. It’s not just the pain of loss, but also the pain of engagement itself. MAGA is extraordinarily cruel to its political opponents. But despair is an elite luxury that vulnerable communities cannot afford. If Trump was telling the truth about his intentions — and there is no good reason to think he wasn’t — then he will attempt a campaign of retribution and mass deportation that will fracture families, create chaos in American communities and potentially even result in active-duty troops being deployed to our cities.”

So, while sad and tempted to quit caring, even that, as depressing as it sounds, is “an elite [and selfish] luxury.” Here are my commitments instead:

#1: See. I choose not to give up on my faith commitment to see all people—i.e., to love neighbors, regardless of anything. David Brooks published an important book last year titled, “How to Know a Person,” and his post-election column explained something Will Campbell helped me see long ago, i.e., a “redistribution of respect” that led to a “vast segregation system” between the Political Left and those that now comprise the base of the MAGA movement. Brooks’s post-election column titled, “Voters to Elites: Do You See Me Now?,” reminds me that condescension creates problems and does not cure them, and I won’t abandon my desire to see all people as human beings equally worthy of sincere love and respect.

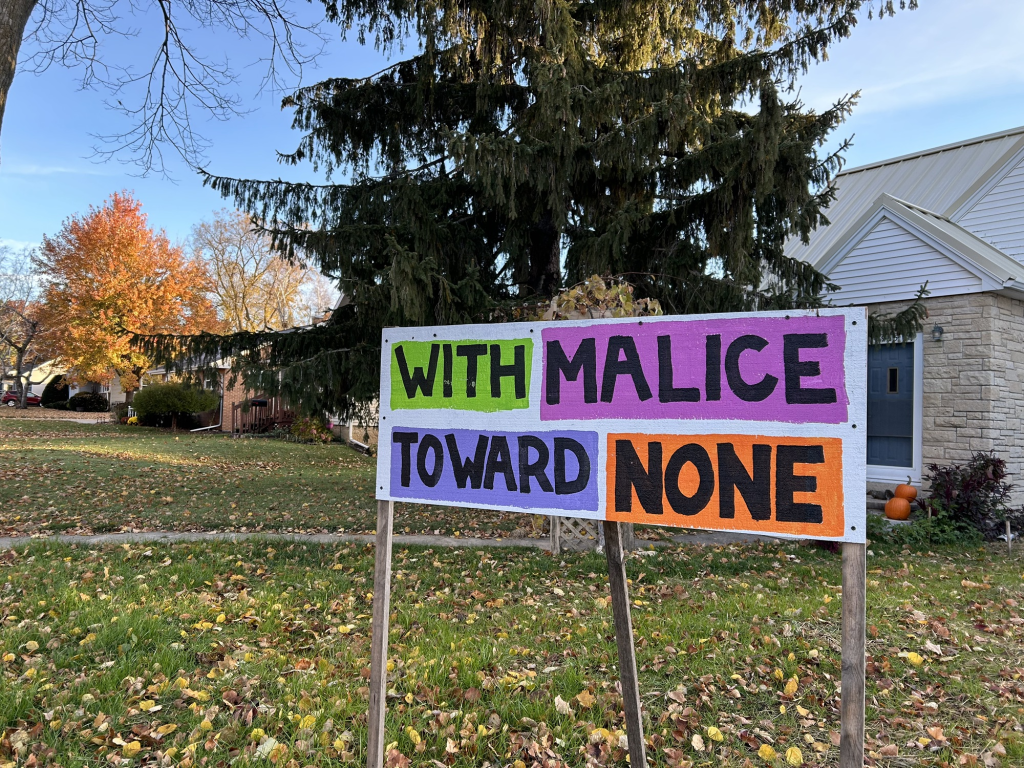

#2: Speak. This, I confess, feels like my greatest challenge. One change I must adopt moving forward is a willingness to speak up more, even though that will risk alienation from and dismissal by people that I love on every side. It is tempting to bite my tongue, especially when I want to remain in relationship with everyone, but I think David French is right when he says we are compelled to “speak the truth.” He explained it this way: “Telling the truth means combating deception and misinformation, but it also means publicly defending the dignity and humanity of the people and communities who are the object of Trump’s wrath. It means resisting malice when we encounter it in our churches and communities.” Remaining silent might appear to preserve relationships, but it forecloses all prospects for true justice and real harmony. This blog post is an initial and meager attempt to speak up more.

#3: Act. Finally, as hard as the first two are to do, they are insufficient without action. David French wrote that we must “protect the vulnerable,” but I like how Dr. Tressie said it best: “Don’t cry too long over a sinking ship. Build dinghies.” To continue the nautical metaphor, the Brooks column concluded this way: “[W]e are entering a period of white water. Trump is a sower of chaos, not fascism. Over the next few years, a plague of disorder will descend upon America, and maybe the world, shaking everything loose. If you hate polarization, just wait until we experience global disorder. But in chaos there’s opportunity for a new society and a new response to the Trumpian political, economic and psychological assault. These are the times that try people’s souls, and we’ll see what we are made of.”

I want my soul to pass this test, so with thanks to Dr. Tressie and the two Davids, and after much reflection, I have concluded that it takes all three: See. Speak. Act. Looking backward in despair, looking inward in contemplation, and now looking forward with resolve, that is what I commit to do.